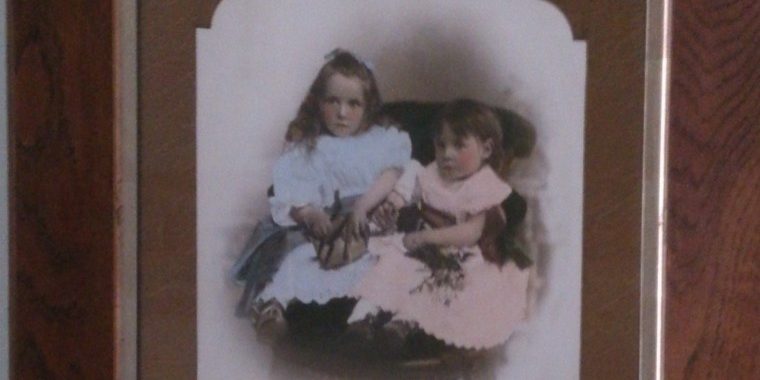

Two little girls, one wearing pink, the other wearing blue, sit together on a velvet chair staring straight ahead with no sign of a smile.

They watch from behind a large wooden frame. On the back of the frame, there is a label that reads:

- Parker, portrait painter and general artist, Imperial Art Studio, Grey Street, Gisborne.

The photograph was taken in 1894 in Gisborne, a small city on the east coast of New Zealand’s North Island.

The girl in blue is my grandmother. Her name was Elizabeth Norma Aube Johnstone, she was always called Aube. She was born on October 10, 1891. The girl in pink is her sister, Dulcia Irene Catherine, Dulcie for short. She was born on October 31, 1892. They are the eldest of seven children born to George John Alexander Johnstone and Sara Catherine Greene.

Grandma and Biddy

Grandma was tiny. At her tallest she barely hit 4’. 11” but what she lacked in size, she made up for in feistiness and speed. She walked fast, she talked fast and she thought fast. She was the first and maybe the only person I ever met who seemed to like me more than my charming younger brother Stuart. Of course, she never said that in so many words. She wasn’t one for lovey-dovey stuff. But I knew she loved me, and I loved her. She called me Biddy or Bridget, I have no idea why.

I remember her mostly in three places; her church, her kitchen, and outside in the garden.

At church, Grandma stood out from all the others. Despite her tiny frame and her obedience to the teachings of the Exclusive Brethren — a fundamentalist, Christian group that uses cult-like tactics to control its members, where women are barely seen and definitely not heard — you could both see and hear my grandmother. Not only Brethren women, but all women wore muted colours like grey, navy and maroon. Not Grandma. She was into blue and green which were not even considered by the most fashionable worldly women to be colours you would wear together. There was nothing muted about the blues and greens that Grandma chose and she wore them with pride.

“If it was good enough for the Lord our God to make the sky blue and the grass green, then it is good enough for me to wear those colours,” she would say.

While she couldn’t participate in the preaching or the discussions she could be heard in her own way by singing the hymns louder than anyone else. Her high-pitched, wobbly, somewhat out-of-tune voice could be heard from outside the meeting hall.

In the kitchen, she was like a bolt of lightning. She could get from one end of the long farm kitchen to the other before my eyes could register what she was doing. One minute she’d be top-and-tailing green beans and slicing carrots at the kitchen table and, the next thing she’d have run the length of the room, jumped onto the counter, climbed up into a top cupboard, grabbed a jar of preserved tomatoes and be back stirring the pot of stew bubbling away on the wood stove.

It seemed to me, that in Grandma’s kitchen, there was always a delicious smell of fresh-picked strawberries and lemonade made from the lemons in her garden. Each time she opened the door to the tiny refrigerator a gentle waft of newly churned, soft yellowy butter and thick, luscious cream brought in from the milking shed would fill the air. Sometimes, especially when I was visiting, at the top of the little refrigerator in the ice box she would have ice cream she’d made from that fresh cream and the delicious strawberries, or peaches, or nectarines or whatever she picked that day.

Outside, she was a force to be reckoned with. Grandpa, who was officially in charge of this area, would gracefully accept that Grandma was the actual boss of everything except the horses, the dogs and the sheep.

Whether it was climbing a long ladder so she could reach the fruit at the top of the trees, or crawling into the water tank to clear the leaves away from the drain, Grandma would have the job done while Grandpa was thinking about it.

I was 12 when I first saw the photo of the two little girls. We were in the garden, Grandma was staking the tomatoes, on the Lord’s Day no less, and did not have the time to cut more stakes so she grabbed what she had at hand including the large framed photograph.

I pleaded with her, “Please Grandma don’t make it all dirty. Please can I have this picture”?

“For goodness sakes Biddy,” Grandma replied, “What would you do with that old rubbish?”

Grandma travels the world

Since that day, the photograph of my grandmother and her sister has travelled with me. It first came home to Ashhurst, and then when I was excommunicated from the Exclusive Brethren and forced to leave my family home, the photograph came with me to Auckland. When I went to Australia for a year I left the large framed photograph in storage but we were reunited when I returned.

Grandma and her sister took centre stage at the house I shared with fellow Air New Zealand flight attendants. There were many unexpected visitors and overnight guests to that house and many of them found my particular flat by looking in windows until they spotted Grandma and her sister.

The photograph travelled with me to London. I got married there and Grandma and her sister hung in our Holland Park bedsitting room and later in our flat near Richmond Park. I was so happy then. Life stretched in front of me full of wonderful possibilities.

When my husband and I moved to Canada, the photograph and the rest of our luggage were shipped to Montreal and then by rail to Toronto. Grandma and her sister lived with us in our first apartment at 1,000 Broadview and later at 1512 King Street West, a commune-type living arrangement where everyone got to know my grandmother. Our daughter Tanya arrived while we lived at 1512.

Grandma and her sister were packed up again and stored while we did a year-long trip in an old Volkswagen van throughout Central and South America. After that adventure, we returned to New Zealand and there was Grandma and her sister waiting for us when we arrived. They lived with us at 21 Benbow Street in St. Heliers and then at 31 Milton Road in Mt. Eden. We lived in Mt. Eden when our son Lucas arrived. This, we thought, and I’m sure at some point the little girl in the blue dress thought this too, would be our forever and forever home.

It was not to be. Restless feet drove us back to Toronto and so once again, Grandma and her sister went into a packing box and onto a boat and finally joined us at 31 Kippendavie Avenue in the Beaches where they lived on the wall above the stairs. They oversaw the life of Tanya and Luke from preschool to late teens. They watched the arrival of Kailah, and kept an eye on her from that wall until she was 13.

The kids’ father and I separated while we lived on Kippendavie. Grandma watched me cry and rant and struggle as a single mum. She watched me flourish as I got settled into jobs, started a Registered Retirement Savings Plan and, eventually got my first mortgage and bought out my ex’s share of the house. Grandma helped me hold it together as I took my uneducated Exclusive Brethren self to university and stayed up late into the night studying until it was time to bake the nine dozen muffins I sold to help pay my university fees.

Grandma and her sister came with me when I moved to Victoria. They travelled back and forth between British Columbia and Ontario as I dealt with teenage hormones, chasing my distressed youngest daughter as she struggled to find herself and thought she could do so by crossing the country to live where her father now lived. They were there looking down the first time the police knocked at the door bringing home my out-of-control son. They were there as my oldest daughter grappled with her language-based learning disabilities.

In 2000, I moved from Vancouver back to Toronto and I left Grandma and her sister and almost all my belongings in storage until I was sure returning to Toronto was the right move.

The storage company disappeared with my stuff, including the hand-painted framed photograph of my grandma and her sister. After several months, Grandma found me — well that’s what I like to believe — and eventually, along with most of my belongings, were returned to me in Toronto.

For more than 20 years now, Grandma and her sister have cared for me from above the couch at my current home in Toronto’s Beaches neighbourhood.

Sometimes I look at other photos of my grandmother taken when I was a child. I remember her sharp blue eyes, her thin straggly hair, her snippy way of speaking, and her inability to sit still. But mostly, I remember that warm feeling of being her favourite child.

I wished I had asked her more questions about her life. I thought I had forever. I didn’t.

Grandma and me: Our last time together

At 17 when I left the Exclusive Brethren. I was, in Brethren terms, withdrawn from and subsequently ostracized by friends and family including my grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins.

I was 23 when I stood with a pounding heart knocking on the door that I had entered so many times as a child. Surely, I would be welcome. I had planned this visit for some time. I mused Grandma would open the door because Grandpa would be outside. She’ll bustle me inside and say, “My how you’ve grown up.”

“Charle,” I imagined, she’ll call out to my grandfather who’d be in the shed or one of the nearby paddocks, “See who is here.”

True to my musings, it was Grandma who answered my knock. She didn’t seem surprised to see me.

Without hesitating she said, “You left the light. You departed from the Truth, I cannot allow you in.” And she closed the door.

I didn’t argue. I just turned and walked back down the long driveway edged with purple bougainvillea to the road where my friend was waiting to drive me back to the Gisborne airport.

I didn’t cry. My grandmother taught me, big girls don’t cry.