It was early spring in New Zealand, the end of the August school holidays. I was bored and couldn’t wait for school to start again. I was staring out the window wondering what I would do for the day. I knew I would clean my room, do dishes and peel the potatoes for tea. These things I did every day. But what else?

My thoughts were interrupted by my mother calling, “I want you to go to the butcher and get the meat I ordered yesterday and then to the bakery to get bread and a Sally Lunn. We’re having visitors tomorrow and I have a lot of things to do. You can take Stuart with you.”

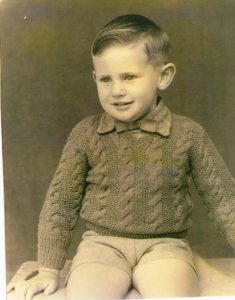

My little brother about three years old

I swelled with pride. I’d been to the shops by myself before but my mother had never asked me to take my little brother with me. He was a handful and Mum thought he would be too much for me to manage. I was almost eight and Stuart was turning six in September.

We set off with our shopping bags, one for the meat and one for the bread. Stuart walked beside me like the perfect little brother. I walked tall with my shoulders back, chest out and head held high.

The trip to the shops was going well. “Mum will be pleased”, I thought.

We got the meat – a leg of lamb – and a lolly from the butcher.

Stuart always got lollies and treats from grownups. I was never so lucky. I heard people say I was too serious, too grownup for my own good. I guessed people didn’t like children who acted like grownups. Or maybe they didn’t like girls. Or maybe they didn’t like children with straight blonde hair. Stuart had dark brown hair and eyes so blue they were almost navy blue. He would kiss old ladies and smile and chat with everyone. I was much more selective as to whom I would kiss or even smile at.

“Go straight home now,” said the butcher.

“We’re going to the bakery first,” I said with great importance. “We’re getting a double loaf and a Sally Lun.”Th

The bread and the Sally Lunn — a large sweet, raisin-strewn bun covered with thick buttery icing, sprinkled with coconut — were ready when we arrived. The smell of fresh bread filled the store.

I couldn`t wait to get home, I hoped my mother would let me break open the loaf and eat the fluffy pieces from the middle. I checked the Sally Lunn, just as I knew Mum would, to make sure it was one with lots of icing and coconut.

We started back home along the main street toward the school but Stuart wanted to take the back road so we could walk home past the paddocks. I didn’t want to but I agreed. I knew I shouldn`t.

He wanted to open the bread bag and break open the loaf to take a little fluffy from the middle. I didn’t want to. But I let him even though I knew the big handful of soft bread he took would be impossible to hide from my mother.

He wanted to carry the bag with the meat, again I let him but I knew I shouldn’t. It wasn`t long before the meat was out of the bag and he was carrying it in the brown paper the butcher had wrapped it in.

I began to think things weren’t going as well as I had imagined.

“Where’s the bag,” I growled at Stuart in a voice I hoped sounded like our mother’s.

I let him stop to look at some cows in the paddock that backed onto Stortford Street, the street we lived on. He wanted to take a shortcut across the paddock. Mum always said we must never cut through the paddocks so this time I stood my ground.

“No Stuart, we`re not allowed,” I said

But Stuart laughed and said, “I going this way,” and he climbed over the old wooden style into the paddock. Some of the cows were chewing their cuds. Others were drinking from the trough. They were all flicking their tails to get rid of the flies that buzzed around them.

They ambled over to the fence to take a closer look at Stuart. He stood about as high as their bellies. He patted one on the rump just like we’d seen our father do a hundred times.

“Come on,” Stuart called out.

“No,” I repeated, “Mum says no.”

Stuart ignored me. By now, even the butcher’s wrapping paper had fallen off the meat. He slung it over his shoulder as if he were a hunter carrying a big game animal.

He started to amble across the paddock. He jumped onto a dried patch of cow dung. He laughed when the patch broke and wet poo splashed all over his gumboots.

“Oh, we’re in trouble now,” I said, “Mum will see the poo and know we’ve gone through the paddock.”

Then I saw the bull in the opposite corner, the corner where Stuart would climb back over the fence onto the road on the other side of the paddock.

“Run Stu, run, there’s a bull, he’s coming to get you,” I screamed as loud as I could.

“Na,” Stuart called back. “He’s a girl bull, he won’t hurt.”

“No, he’s a boy bull, girl bulls are cows.”

I was fairly confident I was right.

And then the bull lifted his head, looked at Stuart and snorted. Stuart dropped the meat, turned and ran back toward me as fast as his six-year-old legs would take him.

Puffing and panting, he climbed back over the fence.

“I not scared,” he claimed once he got his breath back.

“You’re in big trouble,” I said. You dropped the meat and we’re having visitors tomorrow. Mum will be mad. And Dad, he will be even madder when he gets home.”

Except from the bottom of my heart, I knew I was the one in trouble. After all, I was the oldest.

***

While Stuart always loved to joke and tease and never lost that twinkle in his eye, he grew up to be the best brother in the world. Unfortunately, he died in a car accident in 2006. I miss him.